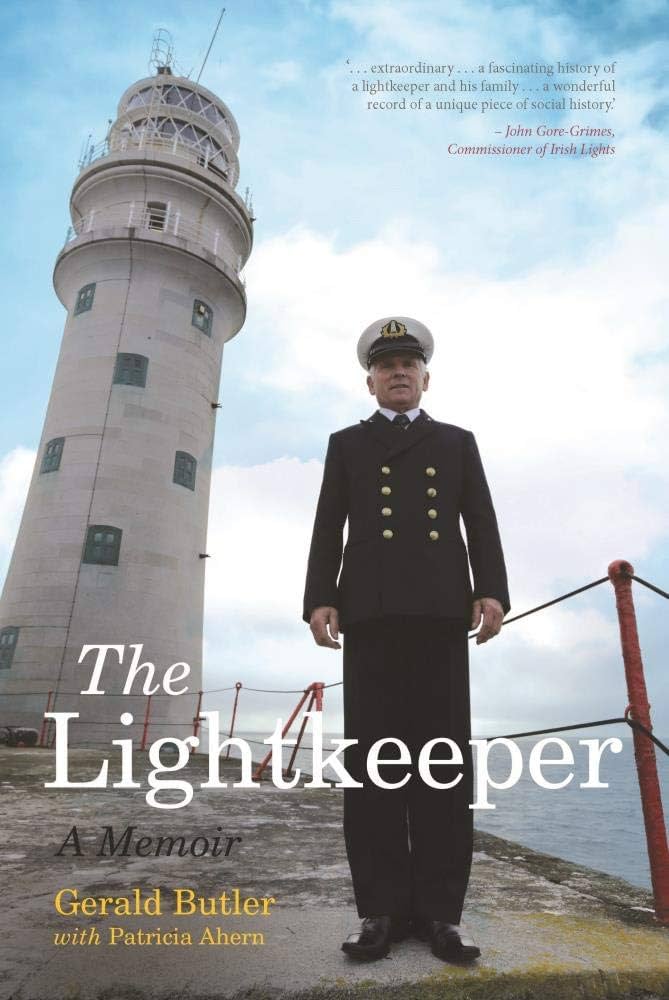

Earlier this week I released ‘The Joys of Lighthouse Keeping‘, an interview with ex-lighthouse keeper, Gerry Butler. This is available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. If podcasts aren’t your cup of tea, the transcript is below. Enjoy!

Introducing Gerry: ex-lighthouse keeper, and current caretaker of Galley Head Lighthouse

Annie: I was fortunate enough to get to interview Gerry, who is the current caretaker of Galley Head Lighthouse in Ireland. He’s had an incredible career looking after Ireland’s lighthouses, so enjoy!

Gerald Butler: Well, Annie, my name is Gerald Butler, and I joined the Irish Lights in 1969 and stayed in it for 21 years until I was made redundant. My parents were lightkeepers. My grandparents were lightkeepers on both sides. I could go back farther because they were on the lightships behind that.

A childhood growing up around lighthouses

I was born in Castletown Bay. My father was stationed on Roancarrigmore Lighthouse. And then we moved from there to the Galley Head. That was only about, I think from what I’ve been told, about two years of age when I came to the Galley. And then we lifted again a couple of years later and headed for Ballycotton in East Cork.

So my father was moving to the different lighthouses. When we were living at the Galley, in early 1950, (19)52 or thereabouts, my grandfather was the principal keeper and my father was the assistant keeper. So the family connection was tying in even at that stage. We moved to Ballycotton. That’s where my mother came from. Her father, who we had just been with at Galley Head, that was his home place. That was where he grew up and all his relations were there as well. Anyway, that’s where I started going to school in Ballycotton.

Moving to Dundalk

Then after four years in Ballycotton we headed up, I think it was four anyway, to Dundalk, just north of Dublin, south of the border. So we were there for two years, but now what was happening at that time? I’m a twin, an identical twin, and we were growing up a little bit. We were becoming a bit of a problem, to put it mildly. And my father used to be out on the lighthouse on Dundalk.

Now the lighthouse on Dundalk was a pile lighthouse like one of the Alexander Mitchell, ah, screw pile lights. And so when he was out on the pile light, my mother was looking after us at home. And it was challenging enough for her, because at night time we’d head off out, we’d slip away. Our family was getting bigger, so my mother was tied down pretty much. And once it get dark in the wintertime, my twin and myself would head off into town. Now we were only 8-10. Oh, when you think of it!

We joined up with gangs and we were going around throwing stones at people’s houses and becoming anything but what we should be. Anyway, we were coming under the notice of the guards, the police. So, my father then requested a transfer from Dundalk to a land station where he could keep control of us, where he could keep an eye on us. And then we came back to the Galley Head.

What happened at Mine Head was the station was being automated and my father was still an assistant keeper. So he was transferred to the Galley, as an assistant keeper. It was a two keeper station. And then when he was promoted, it became a one keeper station. So it was just us on our own, our family.

My father was the principal keeper so they employed my mother as a female assistant keeper. It looked wrong on the books having a lightkeeper on his own. And the history of the Irish Lights going way back into the early 1800s, women often worked as light keepers when they’d be on the outlying rocks.

If a keeper took sick, the woman, his wife or his daughter or whatever would step into the bridge and fill that gap. And so my mother was officially employed as a female assistant keeper.

I was steeped, totally and absolutely steeped in Irish Lights. The lighthouses were my life from the day I was born.

Gerry Butler, December 2024.

Joining the Commissioners of Irish Lights in 1969

Well, in the meantime, I joined the Irish Lights. I joined the Irish lights in 1969. And the Galley was still my home. So I was heading off to wherever I would be working. And for my holidays, or my time off, I was coming back to the Galley.

So if you like, I was steeped, totally and absolutely steeped in Irish Lights. The lighthouses were my life from the day I was born. My twin brother and myself, we joined into the Lights. But strangely enough, he couldn’t, he needed a human interaction with people. Whereas I was quite happy on my own and that was a huge requirement.

So after about five years he had to leave it. He wasn’t able for it. And it’s just the way people are made up, you know. So anyway, I stayed on in it as I say, up until I was made redundant. I joined the Irish Lights in 1969.

As [trainees] we remained at the Baily Lighthouse in County Dublin. And as a call would come in, you went out in your turn. There were 30 of us in the Baily and it was mayhem. What the fun and crack we used to get up to. I mean we’d often have to just take your bed back, put something on the floor in the tower and sleep there. You had to sleep wherever you could throw.

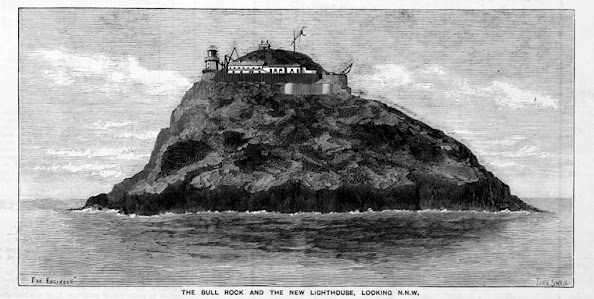

You didn’t even have a mattress to throw on the floor. You just slept there. Then when a call came, whenever somebody went sick on the coast or whatever and your turn came, you headed off with all your sleeping gear. You headed off to wherever the relief would be carried out from. And, so I did that for four years. And in 1973, I was appointed to the Bull Rock. Now, being appointed meant that I was now part of the staff the Bull. I was an assistant keeper and I was coming and going to the Bull Rock.

Keeping Bull Rock Lighthouse

I’d spent my month on the rock, my month at home, my month on the Rock, my month at home. And of course that I love the life so much. It was a dream come true. Living on the Bull – it was a very, very interesting rock.

First of all, I often describe being a lightkeeper, as being a prisoner. You went out, and were sentenced to this prison for a month. You hadn’t committed any crime, but there you had to go.

Annie: But you’ve just said how much you loved it!

Gerald Butler: Yeah. If it was a prison, I’d be committing crimes every day just to get back!

However, so when I went back to the Bull then, or when I went to the Bull, the first thing you’d have to do is order your provisions, your food. So we would phone that into the, grocery in Castletownbere, and they arranged everybody’s food basket. So there was, Inishtrahull, Skellig Michael, Bull Rock, Fastnet. Those stations were all serviced from Castletownbere. So we would phone our, or I would phone in my food order.

And when I get down to Castletownbere, the lady in the shop, she had everything bagged into a market basket for us and I would take my food. A fortnight later I would ring up and I would get a replenishment. Because the reliefs were staggered. There was three keepers on the Rock, which meant that two keepers went ashore. A fortnight later, the third lighthouse keeper went to shore. So when the two keepers went to shore, they were relieved by two. So the third keeper remained on as, an interchange or as an overchange, if you like. Just so that there wasn’t a severance complete severance.

After a fortnight, that bread had gotten very mouldy and stored in the dark cupboards that were just full of little weevil type things. Small, they’d be the same as weevils, maybe a little bit bigger. But you’d see them tearing away when the light shines on them. The bread used to be like a piece of plywood. So you’d get your slice of bread after 10 or 12 days and you’d smack it off the table, and you’d see all these little fellows running away from me. And then I learned very quickly how to make my own brown bread.

So you settled into doing your duty. The duty in the daytime: all it really consisted of was making sure that if the fog closed in, you started the fog signal. If it was wintertime, you’d watch out for when it got dark, which could be quite early in the winter, and you’d light the light. Every Sunday our watches changed. So when you landed on the rock, usually it was a Wednesday. From Wednesday until Sunday, let’s say you were on the 2 to 6 watch. On Sunday the watch has changed. You now moved on to the 6 to 10 watch. The following Sunday you were on from 10 until 2. And the following Sunday you were back again on your 2 to 6, and the watches all rotated around like that. Everybody got a fair crack of the whip.

Similarities between Scottish and Irish Lighthouse Keepers

Annie: Whilst talking about his duties as a lighthouse keeper, Jerry pointed out a number of similarities between Scottish lighthouses and Irish lighthouses and the way they were run. He mentions Ian Duff, who was a prominent member of the Association of Lighthouse Keepers and who passed away earlier this year.

Gerald Butler: I remember Lord mercy on Ian Duff. Ian came over to Ireland in 2013 and that was the year we were doing, the year of the gathering in Ireland. So we were doing a lighthouse keepers gathering and Ian came over and joined into that, and it was fantastic just to have him there because RTE brought us up into a room where we were out of the way of everybody who was there. They interviewed us and when they did, Ian was there with us.

And you would think that Ian was an Irish lightkeeper or we were Scottish. The work we did, the language we spoke, everything in between was the exact identical same. So you could say that no matter where you are, if it’s America or anywhere on Europe, that it was always pretty much the same type of work we all did.

The Magic of the Bull Rock Lighthouse

The Bull Rock has a huge big arch passing through the bottom of it. You could drive a 30 or 40 foot fishing boat through it.

So it’s steeped in Irish mythological history as well. It goes back to about 1400 BC when the sons of Milesians were invading Ireland. So you have the Bull, the Cow, the Calf and the Heifer rocks. They’re a family of rocks that are just off the Dursey Island. So about two and a half miles south or maybe east perhaps of the Bull is the Calf Rock.

So the story kind of goes, it’s all myth now that the sons of Milesians were shipwrecked off the Irish coast. And Donn was the eldest of the brothers. He was shipwrecked, either on the Calf Rock somewhere there, but his body was supposed to have been buried on the book. And he being the eldest of the brothers, was elevated or promoted to Lord of the Dead. So at Halloween every year, Donn would blow his trumpet and the souls of all the dead for that year would amass at the bottom of the Bull and Donn would send them through the arch across the ocean into eternity.

Christian mythology is a little bit different. They say, it’s all the souls on their way to eternal damnation pass through. Can you imagine knowing that and being out there?

The bird colonies of Bull Rock, and their lessons about loneliness

So it’s a fascinating place. It’s a gannet colony. At that time there were three gannet colonies in Ireland: Little Skelligs, Bull Rock and the Saltee Islands.

The gannet, is a bird that spent its entire life at sea. If it landed in a field, it cannot become airborne, so all of its life is spent at sea. And having a gannet colony on the rock meant it was a great interest, because you were watching these birds every evening. You were watching them building, you were watching them feeding their young, you were watching the mating, you were watching them courting, you were watching everything about them.

On the opposite side of the rock there was another colony of kittiwakes, ah razorbills, guillemots, all the auks, and the seagulls. You had all of this going on on one side and you had the gannets on the other.

Now the kittiwakes, they make a huge amount of noise. They arrive, we think it’s around the 23rd of December and they’re just flying onto the rock and leaving sometime in perhaps March, April. And then they start building.

We think it’s that they wait until the highest tide in the year has passed and they know then how low they can go with their nests. Then they would start building and they’d be busy, busy, busy fishing and feeding their young and teaching them how to fly and all to that. And then on 23rd August. It’s one thing I will never ever forget.

Every day I used to go over to where the [birds were]. And I would spend ages just watching them. And I went over then on either the 23rd or 24th and they were gone overnight. They disappeared. Mother of goodness.

The silence was the most horrible, horrible thing that I experienced. And that created a loneliness. And it taught me something about being lonely. It taught me that loneliness is either not wanting to be where you are, or else wanting to be somewhere else. So I wanted perhaps to be where that noise was. Wherever the kittiwakes were gone. I would have loved to have been able to follow them and spend the next six months watching them there.

Gerry Butler, December 2024.

It didn’t really to me mean not wanting to be on the Bull Rock because I absolutely loved it. But it was a strange experience.

Transferring to Fastnet Lighthouse

I got transferred from Bull Rock to Fastnet. I actually applied for that transfer because I was having a bit of difficulty with another keeper who had come to the station. We weren’t going to get on so I requested a transfer. And the chap who was on the Fastnet did not want to be there at all.

Fastnet could be seen as a punishment station. If you were misbehaving; if the Irish Lights thought that you were becoming a bit of a problem, they might send you to Fastnet. So I think they were a bit surprised when I applied to go there!

But anyway, I loved the Fastnet. Fastnet was a completely different experience because we lived in the tower. So we shared a bedroom. The room was round, and there were three bunks in the bedroom. There were two bedrooms. One for visiting tradesmen or workmen or technicians and the other was for the keepers.

So if there was no technician or tradesman on the rock, one of the keepers would move into the workmen’s, not use up all the air in the bedroom.

Annie: To have some space.

Gerald Butler: Yeah, have a bit of space, anyway, so there was no privacy on Fastnet. You didn’t need it and you didn’t care about it either. It was very confined. I’m kind of small so it suited me down to the ground. I was able to fit into every little nook and cranny that there was.

I loved the Fastnet for the dramatics that you’d experience on the rock. On the Fastnet the watch keeping was the exact same. The fog signal was more labour intensive than the Bull because we would fire explosive fog signals. And Fastnet was raided during the Irish War of Independence, the IRA raided it. The IRA raided nearly all of the lighthouses during the Irish War of Independence because there was explosives at most of them and detonators and etc., etc. So they needed that for their activities.

And it ultimately meant that the Irish lights had to discontinue using explosive fog signals until the country settled down again. I say about 1924 when the country is settled back down again.

The Irish lights got back into using the explosives so the watch keeping was the same and etc.

The Dangers of Fastnet Lighthouse

But the weather on the Fastnet could change very, very, very, very fast soon as the wind would shift up to the west. I remember being out on top of the pad walking at 3 o’clock in the morning and you’d become very, very conscious of the wind direction. You’d know that absolutely all of the time. It was just innate knowing it.

You just had to know it and you knew it. And so I was on it. The wind shifted to the west, let’s say around 10 past 3 in the morning. And at 20 past the first wave came up on top of the rock. I had to get in after that. You couldn’t stay out beyond that.

What happens is at sea, the waves in a storm, when low pressure etc. plays its part on it as well, the waves would rise, the rise and fall would be 30, maybe 40ft high. And then when the wave moves in onto the shallower ground there’s a ledge, maybe about a half a mile or there’s something about a half mile west of the Fastnet. That will cause the wave to nearly double in height.

So now the wave would be coming at the lighthouse, it’d be charging at it at a phenomenal speed. I estimated somewhere in the region about 60 miles an hour. For modesty you could say 40 or 50 easily and you wouldn’t be anywhere wrong with that. But when that water would hit the Fastnet the first thing it does is it traps pockets of air down in around the rock.

And the wave is moving so fast, it’s the top of the wave now gets blown off first. It’s moving with so much speed that the air doesn’t have time to escape. So it’s compressed on top, dead centre, hits on top of it, it compresses the wave and then there’s this explosion. So with that, the air then tears into the wave, into the incoming wave and it gives the wave, the heal that it requires to lift thousands up on top of more thousands, tonnes of water.

The light is 163ft over sea level and the sea would leave it for dead. It would easily go 34 to 50ft over it depending on what the storm was like. When that happens and you’re inside in the lighthouse, everything is locked up now and you’d hear the explosion with the way of doing its business and then you’d hear the rush of water coming up. Also, you’d feel the air compressing inside the tower.

So what I used to do was I race over to the barometer just to have a look at the barometer needle and you’d see the needle and it, it move quite vigorously. Then when the wave would come right up and wash over the tower, maybe at that point or a little less than that point, the tower would vibrate.

Now the vibration can be 3ft off centre, which is a huge vibration, a huge amount for the tower to sway. But what I found on it, in every winter storm anyway, was that when this would be happening (and that’s the sequence that I just explained to you). In every one of those, almost every one of them, there was one wave that would perform differently to the rest. They say there’s a black sheep in every family. Well there’s a black wave if you like!

And what happened on the Fastnet was we’d hear absolutely nothing at all and then the wave would just strike the tower. So what we reckoned that happened was all the water would pull away from the rock, meet up with the incoming wave and strike the tower very high up on top. So inside the kitchen you had all this water, tonnes, maybe thousands of tonnes of it, just crashing at your kitchen wall and that caused the tower to sway so much that I was standing in the middle of the kitchen and the weight trunk was passing down through the lighthouse and I was holding on to the kitchen sink which was one of the cupboards around the weight trunk. If I did not put my foot out to correct my balance I would have fallen on the ground.

On another occasion in 1986 a wave hit the tower again, something like that. And the lens, which are floating in a bath of mercury (and the lens on fastened weighed six tonne), and they leaned over so the jolt was so hard that it caused the tower to tilt so much that the lens leaned over.

When the lens splurged back into the mercury again to regain their balance, about a pint of mercury at least came jumping out of the trough and spilled all down through the lighthouse. You can get very, very, very dramatic weather on the Fastnet. And, I loved it for that because to experience that, was, ah, terrific in itself. I mean, I won’t experience that again.

Annie: Yeah. Were you ever worried that the tower would come down if it was swaying that much?

Gerald Butler: I didn’t because I, think that all of that, a sense of fear, if you like, depends on what age you are. When you’re young, you couldn’t care. When you’re older, you might be different, you might think differently about it. But anyway, I didn’t. I loved every single thing about it.

Serving as a lighthouse keeper during the Fastnet Race Disaster, 1979

I loved the dramatics of that and I worked on it in 1979 and during the Admiral Cup Yacht Race. And in that year it turned out to be an absolute horrible disaster.

What was happening that night? As the yachts were coming along, now okay, we know that weather reporting was so much different than to what it is now. There is a bank, a sand bank, and it’s about halfway between Ireland and England. Very good fishing ground.

When the waves move in onto shallower ground, even though the sand bank is a couple of hundred feet deep, nonetheless, it’s shallower than a lot of the water around it. So on top of the bank, ah, the storm was extremely violent.

So yachts that were caught up in that place at that time, they were rising away up 40ft in the air, and then the wave would collapse beneath them and the yacht would come charging down off the wave and crashing into the trough and the bottom. And of course, completely out of control.

If the bow dipped down it yacht would go head over heels, cartwheeling. If it was broadside on the yacht to just flip over on its side upside down and come up the other way around again. And can you imagine being inside in the cabin, inside, down below in the yacht? Ah, when that’s happening, the cupboards were breaking open, the bean tins, the tins of sardines, everything, they were like missiles flying around inside them.

People that were caught inside that were getting the daylights battered out of them. They were bruised and battered anyway you could think of. So we were listening anyway, on the 21A2. 21A2 is the distress frequency. It’s also the calling frequency on the medium wave radio.

This was pre-VHF radio, so that’s all we had. But these radios we had were very powerful. So we were able- you could easily hear a couple of hundred miles radius in it at night time. In the daytime it a drop back maybe to about 150 miles. But at nighttime the range of these radios was colossal.

So we were able to hear without any difficulty all the mayhem that was going on. So yachts said come on, they put out their mayday and they would say what happened to them. The others would come on and make, made a relay, say they passed the yacht. No sign of any life or anything in the yacht is just helplessly ah, drifting there. It could well be that the people were still inside the yacht but not coming out on deck. And more people would come on and say we’ve just passed the yacht and it’s totally capsized that we can’t see anybody in it.

Somebody else would come on then say we’re after passing another yacht and they’re clinging onto the side of it. So a yacht could not stop to help another. So if you saw someone in difficulty, forget about helping him. Because if you did you were then going to be needing help yourself. So you were just adding to the difficulty. That went on all night long. So all we could do was listen to it. Ah, I had called out the Baltimore lifeboat about 10 o’clock that night for boat that had come near the Fastnet. Now at that time the sea was quite calm when the boat came out about 3 in the afternoon.

But by 10 at night the sea was raging and I was watching that yacht’s lights disappear and I didn’t know whether that was after capsizing, sinking. I didn’t know what was going on, and maybe nothing. So I got the lifeboat launched for that. They never found it. And then I think it was around midnight or thereabouts that there were others that got in difficulty about a mile and a half south east of the Fastnet.

Once the rudder went in the yacht and that’s what was happening, the rudder were just snapping off them. The yacht was helpless and it would turn broadside onto the weather. So they streamed ropes from the bow of the yacht just to keep the head up to the waves. The wind was blowing these yachts now right in our direction to the Fastnet.

They were only half mile and a half east of us or southwest of us, which was too close for this to be happening anyhow. The Baltimore lifeboat finally caught up with it. The Navy were standing by and they had them regardless, pinpointed. So the lifeboat was able to (it was about 15 yachts in the area) [and] the lifeboat was able to take it on tow and back into Baltimore. But that towing line parted about five times on the way in.

That will give you an idea of how high the waves were. So that tragedy. Yeah, it was an absolute desperate tragedy altogether.

Transferring to the Old Head of Kinsale

The end of that year, 1979, I was transferred from the Fastnet to the Old Head of Kinsale. The Old Head of Kinsale is a headland relieving station. I was building my house at home at that time. I got married and I was building my house at home and it was very handy to me at the Old Head. It was only about, maybe a half an hour away from me. I had a little Honda 50 motorbike and I used to head over and back and do some of the building on this house myself. Took me a couple of years to get it done, but the house is built now and I’m happily living inside it.

Annie: Very impressive. Very impressive.

Gerald Butler: Yeah, great. So, yeah, I stayed at the Old Head for two years and then I was transferred to Mizen Head and I spent nine years at Mizen Head. And I absolutely loved, my nine years at the Mizen.

The life you’d spent in the Irish Lights was just so exciting. I didn’t care where you were, didn’t matter. I used to spend a lot of time diving, so I’d be snorkelling, diving down, swimming around, looking for crayfish, and you’d get quite a few of them.

Climbing if you were on like a Skelligs or Tearaghts or even the Bull, you could do quite a lot of rock climbing. You had to be careful, and things were great when you were. My father, God rest him, brought us out to Ballycotton when I was four. And the seed was planted. If it wasn’t planted before, that was certainly planted then. [In] 1990, somebody invented the microchip. If I had my hands on them, I would choke them. My job was gone.

Gerry’s current role at Galley Head lighthouse

Annie: Now, are you back at Galley Head?

Gerald Butler: After my father retired as an attendant keeper at the Galley, my mother became the attendant, oh sorry, my father died, my mother became the attendant, and then when she retired, I applied for the position as the attendant keeper. And I’m still the attendant keeper there. That’ll change now next year. And I can’t say I hope it won’t because that might mean I won’t be around, and so we won’t go there.

Annie: So what are your roles as an attendant at Galley Head?

Gerald Butler: Well, it’s really health and safety of the station, so you’re given the responsibility of making sure that the place is secure. The Galley Head has a very low cliff wall, boundary wall surrounding it, so people can come in, jump up on top of that cliff wall and they’re exposed to extreme danger. So you have that responsibility.

The light itself, if anything goes wrong with the light at night, there is a good backup system there, and it’s monitored and it’s now monitored from Harwich in the uk. Yeah, if it’s after dark and at the weekends, so, I’d get a phone call if the bulb failed up at the Galley. I’d get a phone call from Harwich telling me what I already know. And I’d go up then and I’d fix whatever is gone.

If I can’t, the Irish Lights then would issue a notice to mariners, a radio navigation warning and in the following morning then did send on a technician to carry out what repairs needed to be done.

My role is part time if you like. Even though I say it’s full time work with part time pay, I still don’t mind because I would pay to do the work anyway.

All that said and done, it was life changing and nobody wanted it. Lads who were coming close to their pension, they hated it as well because you’d look at your own life in it and say: what was it all for? Is this the end? Is this it? Just draw a line through it and we go off in a different direction, that we’re no longer needed?

In my own case, which is all I can really talk about, I was just under 40 years of age and I had been watching the other lightkeepers and I reckoned from the age of 40 onwards, they were not as fit as I would like to have been. And I was, when it came to it, like the redundancy that I took was a voluntary redundancy now. Voluntary. How are you? I was, it was Hobson’s choice. But you were going to be given a little bit of extra time. So I might have lasted maybe another two years, five years, that would have been it.

So I was under 40 and I reckoned that I was fit enough to start something else. And that’s what I did. That was my reason for taking the redundancy package at that particular time.

I suppose in a way I was looking ahead and not looking back and I wasn’t conscious of that at the time, but that’s what I was doing, so that probably helped as well. And shortly after that I was asked by a local historical society while I was fishing, would I, give a lecture on the history of the Galley Head. And I did.

And that opened up a complete new life for me because I started into the research. I knew it anyway, but I wasn’t that conscious that I knew as much as I did about it.

And with the research, I’ve been given that, those lectures for the last 20, 25, maybe more years, you know.

When I’d be doing these lectures I would be asked, would I write a book? And I was told, you should write a book. And I could talk about lighthouses in so many different tangents. And you say, “not at all. The books are all done, forget them.”

I have about 30 or 40 them up on my shelf and they’re gathering dust and [it would be] another one just to add to the heap. And this lady rang me and I had declined to do it. And I remember she said to me, well, would you make a DVD? And I thought about it, said okay, as far as I know that hasn’t been done.

So we talked about it a little bit, and I got to thinking about it and that’s what I was doing. I was running it around in my mind. How would you do it? How would you get back to these place? You’d have to photograph them, you’d have to show. You’d have to. This.

The Irish lights rang me, and they told me that this lady was onto them and she wanted to write a book and could they give her my name? So I laughed and said, “yeah, you can. But I said I’m not going to do it.”

So the lady came here and she sat in the couch here in the kitchen and I did my utmost to talk her out of it. And she said to me, I’m going to do it anyway.

And something changed in me as soon as I heard that. And often people need that reassuredness that this is going to be done. So I said to her, well look, if you’re that determined to do it, I’ll help you. Because I said I have, I have all the information you’re going to need.

I loved that life. I absolutely loved it for every single thing that it could give. The adventure, the closeness to nature, if you were involved in a rescue, the experience of that and, the dramatics of it, every bit of it was just there to enjoy or to love it.